35 quick edits to improve your script's writing style in 24 hours or less.

A reader knows from the very first page whether the writer knows how to write. It’s clear from the dialogue, formatting and writing style. It's clear from the way the writer chooses how to put the images they want the reader to see down on the page.

However, there are quite a few mistakes and odd stylistic choices that we see writers make again and again. Mistakes that pro writers don’t generally make.

Go through your screenplay, cutting all of the following writing style mistakes and make it feel more professional in one day or less.

1. Strange/awkward acting demands.

Often it’s clear what the writer intends with phrases like these, but another way needs to be found to get the action or emotion across. Always aim to direct actors as little as possible and let the circumstances of the scene suggest how they should play it.

Very often this means simply leaving out any specific instructions on what they should do with their face or body.

2. Car porn.

Unless you’re writing a Fast And Furious-style movie in which high-end car makes could be important, leave these kinds of descriptions out.

There’s a difference, however, between car porn and naming a car as an additional way of showing a character’s personality. This description from Sideways is a good example of the latter:

3. Missing hyphens.

If you’re prone to leaving out hyphens, brush up on how they should be applied and make sure you get them in your scene description and dialogue. The above examples should read like this:

4. Writing style full of clichés.

A good way of catching many cliches is to simply ask yourself if you’ve seen or heard that particular phrase before? If the answer’s yes, take another look to check if it’s a cliché.

Do a Cmd+F search on your script for these most common offenders in spec scripts, all of which involve eyes for some reason: “his eyes widen” “her eyes narrow” “he rolls his eyes”.

Also, do a search for the phrase “like a…” as anything that follows could well be a cliché.

5. Summarizing action.

A writing style like this indicates the writer has forgotten that film is a visual medium. Everything you put down in the description will be visualized by the reader, and so missing out action and summarizing instead always leaves the reader confused.

Either use a MONTAGE or add in the missing action or dialogue.

6. Unnecessary repetition.

Repeating either a word or phrase or a character’s action means you’re taking up valuable real estate on the page, while also giving the reader the impression you’re not aware of it and so aren’t fully in control of your writing style.

7. Half-finished words.

It’s best not to cut off words like this as it looks odd on the page and often leads to confusion. Write out the whole word add some ellipses and leave it to the actor to decide how to trail it off mid-sentence.

8. Naked sluglines.

A slugline should usually be followed by description of some kind. Otherwise, it’s “naked” and the scene hasn’t been properly established.

9. Stating the obvious.

Again, this feels like redundant writing because it’s clear in the reader’s mind what’s happening, but the writer is feeling the need to spell everything out anyway—in effect, twice.

We know, for example, that if someone's staring at someone it's in their eyes, or if they're pacing it's on the floor, and so this writing style can definitely be tightened up.

10. Ellipses overload.

Ellipses can be effective, but use too many of them and they can slow down the read and start to feel like overkill.

11. Parenthetical extravaganza.

An overuse of parentheticals means you’re again over-directing the actors, which they're not too fond of. Instead, give them room to insert pauses or beats where they see fit.

12. Purple prose writing style.

An overly descriptive, flowery writing style like this belongs in a novel not a screenplay. Keep things simple by cutting all instances of purple prose like this.

13. Restrictive character descriptions.

The problem with detailing physical features in descriptions is that you're ruling out many actors who could play the role. It’s always better to stick to a character’s actions, overall style, attitude, clothes, make-up, etc. in order to clue us in on their character.

14. Mixed emotions.

Lines like these are simply confusing, both for the reader and the actor. Pick just one emotion that you want to get across in any given moment.

15. Impossible/unrealistic acting demands.

As with mixed emotions, these actions are pretty much impossible for any actor to pull off.

Make sure you always put yourself in the actor's shoes when telling them what to do and think “How would I play this?”

This should help prevent coming up with impossible feats for them to perform.

16. Missing full stops.

Some writers forget to include full stops in their sentences and break up long paragraphs into smaller chunks. Don't be one of them. Give the reader a chance to breathe.

17. Unnecessary sounds.

Sounds only really need to be included if they’re necessary to our understanding of what’s going on in the scene. All of the above examples offer no new information or anything to the scene, so can be cut.

18. Back to front/passive writing style.

A better way to phrase these would be:

Note how the second examples not only feel more active rather than passive but also enable you to more easily visualize what's happening.

19. Micro-managing actors' actions.

Both of these examples could be cut back to:

Not every action an actor makes needs to be spelled out. You'd be surprised at how much the reader fills in for him or herself.

20. Overusing character names.

This feels unnatural because in real life no-one uses the name of the person they're speaking to that often.

It's a good idea to get the characters' names out there at the beginning of the script, but if we're halfway through, there's no need for everyone to still be bringing up each other's names in every line.

21. Overly formal language.

This is a big one. So many spec screenplays contain a lack of contractions in the dialogue—we’re, didn’t, they’ll, I’m, don’t etc.—that the conversations just end up feeling unnatural and stilted.

The only time you really want to have your characters talk like this is if it’s on purpose because your script is set in the 1800s. Or you want a particular character to speak in a super formal manner, say, because of their occupation.

22. Basic grammatical errors.

Here's a quick list of the most common mistakes we see in spec scripts, so make sure you really nail their uses:

• its/it’s

• off/of

• lie/lay

• waits/awaits

• your/you’re

• whose/who’s

• to/two/too

• their/there/they’re

23. Basic spelling errors.

Spelling errors of basic words like lose, breathe, peek, etc. don’t give a good impression either.

No matter how good the script, a reader will automatically begin to question your overall writing ability if it's peppered with mistakes like these.

24. Similar character names.

When the protagonist's called Tim, and then we meet his best friend, Tom, and then they both fall for a girl called Tina, you're unnecessarily confusing the reader.

Likewise, if you have three women in a script named Lucy, Tracy and Wendy. If more than one character name either starts or ends with the same letter, take another look and see if it needs changing.

Similar sounding names often result in the reader constantly having to flip back through the script to check who's who.

25. Unnecessary exclamation marks.

Exclamation marks look particularly incongruous in dramas, thrillers and horrors and are best avoided in these genres. You can maybe get away with a few in comedy, family or action/adventure scripts, but use with caution!!! (See how over the top that looks?)

26. Omitting character names.

Often characters remain as MOM, APPRENTICE, DETECTIVE, etc. throughout the whole script when really they should be given names. A good rule of thumb to go by is: if a character has more than a couple of lines of dialogue they should be named.

Again, think about your script from the actor's point of view. They will want to bring as much as possible to their role, but if they’re just the RECEPTIONIST, you’re not giving them much to work with.

Give every single role in the script a sense of meaning and a reason for being there and the actors will thank you for it.

27. Using a writing style that misses out "a" and "the."

This style can work to a certain extent, usually in action movies like Tony Gilroy’s script for The Bourne Identity, but it can also be overdone.

You may have been told that things look more "screenplay-like" if these words are omitted, but it's not true. There's nothing wrong with writing "A car pulls into the parking lot."

28. Excessive use of MONTAGE and FLASHBACK.

While both devices can be extremely useful tools in a screenwriter’s arsenal, many specs overuse them. Be sure that every MONTAGE or FLASHBACK progresses the story in some way, rather than being used to merely pass time in the protagonist's life, or having them reminisce aimlessly.

Also, be sure the formatting is clear. There is no “right” way, but it’s important that they’re well-presented on the page. Check out this page on screenplay format for more info.

29. Excess description.

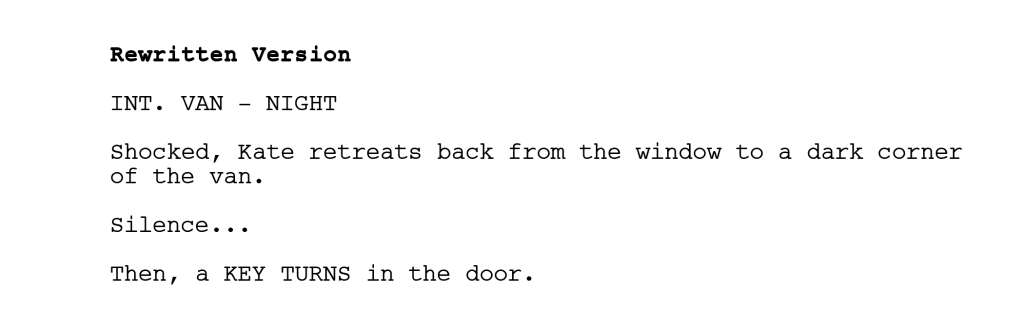

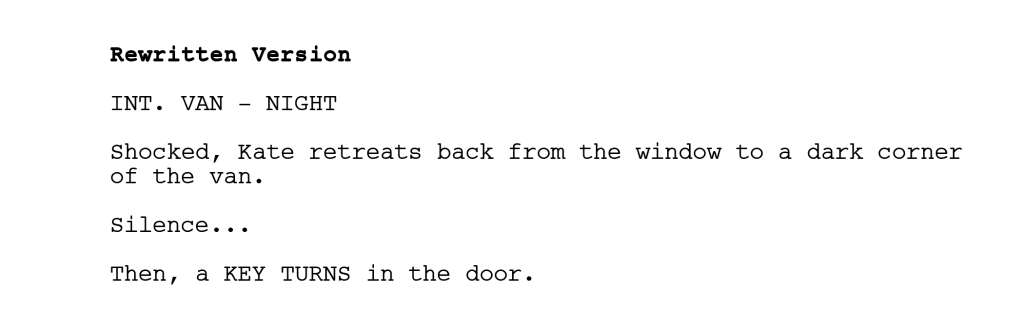

All of this could be written in a much more sparse way that doesn’t spell out every single beat and the actor’s movements. Something like:

This is saying the same thing but in three lines instead of seven. We know Kate is scared in this situation, for example, so we don’t need to be told that she holds a hand to her mouth, or tries to collect herself.

Our Line Edit service is a great option if you'd like a pro screenwriter to go through your script and tighten it up in this way.

30. Incorrectly formatted numbers.

These should be:

All numbers under ten in dialogue should be spelled out as well as numbers at the beginning of a sentence, whether in dialogue or description. Dates and times, on the other hand, should generally be written numerically.

31. Unnecessarily sexualized writing style for female characters.

Unless a woman’s sexuality is essential to her character, it’s best to edit these kinds of descriptions out as they just look gratuitous and slightly creepy.

32. Confusing (O.S.) with (V.O.) and vice versa.

When a character is speaking (O.S.) they’re off-screen, i.e. in the same scene but maybe another room. If they’re talking (V.O.) they’re not in the scene but in a different location altogether and talking in voiceover, i.e. talking on the other end of phone lines, on TVs, or narrating.

So in the above examples, Ted's dialogue should be (V.O.) and Sandra's (O.S.).

33. Copyright paranoia.

Yes, it's a good idea to copyright your script at the WGA West or US Copyright Office, but it's not such a good move to give the impression you're paranoid about someone stealing your script.

This is achieved by including WGA registration numbers, copyright symbols, all rights reserved notices, and especially watermarked pages.

Anything more than adding the title of your script and (minimal) contact information can look a little amateurish.

34. Alternating between single and double spacing.

There’s no correct way to use spacings after periods in a screenplay. Some writers prefer single, others prefer double. What doesn’t look so great is continually switching between the two.

Run a Cmd+F search on “. ” (full stop, single space). Then hit Replace with “. ” (full stop, double space), or vice versa. That will make sure they’re all identical throughout the script.

35. Vowel overkill.

You can get away with a few (such as Aaarrgghh!) on occasion because they don’t distort the actual original words, as in the above examples.

To be on the safe side, a better way to get emotions across in dialogue is to simply write the word normally and leave it up to the actor how they want to deliver it. For example, What?! Stop! Fire!

###

We hope you found our top 35 dialogue, formatting and writing style mistakes useful. There are many more to look out for, of course, but our general advice is to keep your writing style as tight and clean and as simple as possible. Put the most evocative images in the reader's mind.

The very best way to learn how to do this is to read professional screenplays.

Download the 50 best screenplays to read, set aside some time every week and see how your style improves over the months as you absorb all influences from the best screenwriters out there.

If you’d like your screenplay reviewed, check out our script coverage services below.

Loved this post? Read more on cultivating a great writing style...

Improve Your Screenplay Scene Description in 10 Min With This Method

How to Make Your Script Writing Style Leverage 100x More Suspense

How to Write a Screenplay: The Secret to Elevating It Above the Ordinary

[© Photo credits: Unsplash]

Thank you, great, and very helpful to see them all in one place: a Pick’n’Mix of mistakes in the cinema foyer just as you’re about to see your film.

Hey Barry, hope you're doing good! Thanks, glad you enjoyed the read.

Thank you for all this great info. I am a new writer just about to start my first edit. I will be using many of these for corrections. I also see a lot that I did correctly.

Glad you found it helpful, Shelly!

Thank you for all this great info. I am a new writer just about to start my first edit. I will using many of these for corrections. I also see a lot that I did correctly.

Very helpful.. thank you

Thanks Sandip!

Thanks for sharing this. Can only hope these were made up examples cos I found myself laughing sooooooo hard. Is that bad???

Thanks for reading, Kitty! They're all real examples.

Very helpful hints. I plan to modify my script ASAP.

Sounds good - thanks, Jerry!

Many thanks. So valuable.

Thanks, Michael, glad you found it helpful!

LOVED THIS WHOLE PAGE. HELPED ME SEE HOW EASY, EDITING UNNECESSARY WORDS, WAS TO MY TRURO SCRIPT. THANKS SCRIPT READER PRO.

Thanks, Peter - best of luck with your script!

Hi. I'm struggling a bit with use of italics or inverted commas for things like writing seen on a door or characters reading texts etc. Any thoughts? Thanks.

BK

In general, quotes are easier to read so most writers go with those.

Thank you, very helpful tips I learnt a lot

Good to hear, thanks Phil 🙂

good-job, guys!!!

Thank you, Oscar!

Suppose, It is raining in the morning.

Slugline must be -

INT. MORNING - RAINING

OR,

INT. RAINING - MORNING

Which one is correct ?

The correct slugline would be: INT. LOCATION - MORNING and then add the fact it's raining in the description.

suppose, It is raining in the morning.

Slugline must be -

INT. RAINING - MORNING

OR

INT. MORNING - RAINING

The correct slugline would be: INT. LOCATION – MORNING and then add the fact it’s raining in the description.

35 Quick edits to improve the writing skills is certainly a wonderful post

Thanks a lot, Bakhshish!

I'm usually suspicious of these sort of do's and don'ts lists when it comes to screenwriting, but these are excellent, fundamental screenwriting tips. I've been a reader for various reputable companies and competitions, and have seen almost all of what's listed above. #27 is one that's become a personal pet-peeve: the absence of the definite article, "the," in the narrative paragraphs. As you suggest, I think this was something going around the past ten-years about keeping your screenwriting active and succinct. I find it odd and distracting. Finding a unique, engaging story to tell is hard enough. Keep the simple stuff simple. Grammar and formatting are the easiest parts to get right.

Thanks for reaching out, Paul. #27 is pretty distracting and dated as you say.

Those examples in #1 and #15 are hilarious 🙂

Great n useful. My thoughts on,

Point 18, example 3 and revision: It depends actually who acts or talks next. If Brenda then I will go with example. Thanks much.

Thank you.

You're welcome, Toluwani.

I love number 9, why do writers always have to state the obvious?

It comes from wanting the reader to understand everything perfectly, without realizing we fill in most details in our mind.

These points have really helped. My writing style will be improved from now on for sure.

Great, thanks, Nicola!

I'm a freelancer reader for several top companies and I agree with all of these. Soooo frustrating to read em day in day out!

Thanks for commenting, Martha!

What one would you say occurs the most in spec scripts?

They're pretty much all equally popular.

Where can I find your phone number do u have one? I want to talk to you about my tv pilot.

We don't have a phone number but feel free to email.

great post I needed this!

Thanks, Scotty!

Please do one on formatting mistakes, like the whole post.

We have a whole book - Master Screenplay Formatting 🙂

Awesome post, thanks SRP!

Thanks for commenting, Matt!

Spot on with this write-up, I really believe MOST writers will benefit from these immensely so thank you!

Thanks, Shawn!

I need someone to check my writing style in screenplay and make sure its professional and good enough to sell it . .

We have a Line Edit service that you can check out here.

Hi,

the writing style is the BLADE.

Thanks for preventing me from the possible bleeding.

You're welcome, William 🙂

I don't see what is wrong with describing a woman as beautiful if want in a script.

Nothing wrong with it, Dave. We were just talking about excessive description.

I love this. Do way too many of these but love this post for pointing them out. Thanks!

That's what the post is for, Valerie!

I think the write of this post is not a writer. What is wrong with "he lays down on the bed"?

It should be he "lies down on the bed." "Lays" is used when something is laid down, like "He lays down the knife."

I have a location/setting that went up in flames. Is it correct to replace it in the aftermath of the fire as, EXT. WELLINGTON'S BURNT UNIT

from, EXT. WELLINGTON'S UNIT/TWENTY-FOUR?

We'd recommend keeping the original as it's ultimately the same location.

No need to change the scene heading but it's not a deal breaker if you do. As long as it's clear to the reader it's okay.

I have done most of these in my scripts over the years. I look back on them now and cringe.

It's all a part of developing as a writer, Blake. 🙂

Great content. I am going to use this during revision.

Great, thanks for the shout-out, Blake!

It's nice to see so much info in one spot. I haven't been writing scripts that long, so I benefit from good advice. Because I am a lifelong writer, experience has taught me to recognize and outrun a few mistakes mentioned. Which is good. But writing is a skill one never masters. A gift that requires a steady hand and an informed mind. Thank you.

Very true - thanks for reaching out, Karen!

I always got confused with VO and OS and OC, thanks for clearing that one up for me!

You're welcome, Shalanda!

Very good post. My writing style will be the better for it. Thank you.

Thanks for the shoutout!

Is it me or is the best screenwriting blog for info like this on the web?

Thanks a lot, Garth!

How can I improve my writing style more than just reading this post?

Reading screenplays is a great way to improve your writing style. We have many posts on this, such as this one.

As a studio reader the one that really bugs me is #1.. Characters doing weird things with their faces. This article is spot on.

I never seem to be able to find the time to write when I get home from work. I keep putting it off and putting it off... 🙁

Have you seen this post on 48 Ways to Become the Most Productive Screenwriter You Know?

#3 #12 #14 I learnt a lot here Thanks you.

That's good to hear, best of luck with the script.

How much is a line edit. Will it go thru my script and stop all these mistakes?

Yes, it will tighten up your dialogue and description. Here's the product page.

Is this for real? Screenwriting should be about expressing yourself. Its a creative endevor not all right and wrong as this post suggests. Shameful.

The mistakes here are shocking. Do you really see all these in spec scripts?

Yes, we do.

Don't go changing every aspect of the language of your script, as often mentioned they have said some scripts can get away with broken language depending on the character your trying to portray. Some scenes need added description to get the movie you want.

I wish to be a screenwriter in Hollywood one day. Can you help?

Have you seen this post on How to Become a Screenwriter?

I probably do more of these than I'd like to admit. Thanks for the heads up.

Now you know what not to do.

This is REALLY helpful to improve my writing style. Thanks Script Readerpro.

Thanks for reaching out, Tommy!

In example 27, you are suggesting that the article “the” is missing before the word further. It should be noted that the word further is misused as it refers to degree and not distance. The word that should have been used is farther which refers to distance.

Thanks, Rick, but we took many of these examples from real scripts so there may be some mistakes in there.

I try to find a way to say an action description that does not take the meaning of the words literally as in, "Her eyes pop". What an unpleasant image!

Spotted a few of these in my screenplay, too. Thanks for sharing this!

I still don't understand the aspect of writing a play without much description, how would it stand out?

I'm an amateur screenwriter. Thanks for sharing these mistakes, I checked my script and I found half of the mistakes you mentioned and corrected them. Cheers guys!

I have read tons of articles about common screenwriting mistakes and nearly all of them mentioned the registration. Why is that a problem? It's not that I'm paranoid, but after working on a screenplay for months, maybe years, it's only natural that I wouldn't want the janitor finding it and submitting it somewhere as his own, right?

It's fine to add "WGA registered" or something if you want but overall it just gives the impression you're worried about people stealing your script, which is very unlikely to actually happen.

Wow. I thought I had this down but I do everyone of the things listed above. Where's the Tweet button??

I thank you for this. . I'm laughing at my scripts now when I see how many of these are in them!

I write word like "Stoooooop" all the time and think it looks good.

Awesome! I was making SO many of these mistakes.

I read scripts for a living and this post is spot on. Why do characters "eyes widen" all the time and "eyes pop"?

I'm doing so many of these it's embarrassing!

What is the best way to state the location within a location in a slug line? INT. HALLWAY, BROOKLYN TECH HS - AFTERNOON, or INT. BROOKLYN TECH HS, HALLWAY - AFTERNOON

Some pro writers have differing views on this but the overall consensus is to go from general to specific. For example,INT. BROOKLYN TECH HS - HALLWAY – AFTERNOON

And most writers suggest sticking to dashes in sluglines rather than mixing in commas.

Thanks for detailing these. Any work can use a tweak at times . Ah, on that note, it seems you wrote V.O. and O.S. appropriately but then mixed up labeling in the example. Should be, Phone call: V.O., Sugar: O.S. 😉

Thanks. The examples are of the wrong way of doing it, though. I've added the clarification: "So in the above examples, Ted's dialogue should be (V.O.) and Sandra's (O.S.)." Cheers!

Great advice. Thanks.

I think I would only question the V.O. and O.S. criteria. I was always taught that "O.S." dialogue is heard by both the character(s) and the audience, whereas "V.O." dialogue is heard only by the audience. Even in a phone conversation, two characters are really in the same scene -- one could potentially be in the next room, even, but out of the camera's view (if the camera were to be panned in a full circle). Fundamentally "not visible on the screen" at the moment the dialogue is delivered. Cutting back and forth in a phone conversation would use "O.S." where the writer suggests a reaction shot rather than showing the speaker. Heck, a phone conversation could be all O.S. with only reaction shots. Admittedly a directorial/editing choice, but often can spin both characters and their stories in a specific direction on the page.

I've always felt examples of "V.O." might be narration, vocalized character's thoughts, the voice of God, etc. Seems to be some disagreement on this particular format option.

Again, thanks for all the tips.

/h